She must have been Apollinaire’s cornflower

Aureoled in the sunlight of Paris;

There is a poem to be written about her runic grace

The poets of Batac have missed, failed to chant.

“Congressman Ferdinand Marcos upon seeing the Young Imelda Romualdez”

Poem by Cesar T. Mella

· · · · · · · · · ·

He came: a magnificent atom

Aureoled in a tradition noteworthy for its

dogged will

In dazzling the stars in these sunbathed

shores

Ferdinand E. Marcos: An Epic

By Guillermo C. de Vega

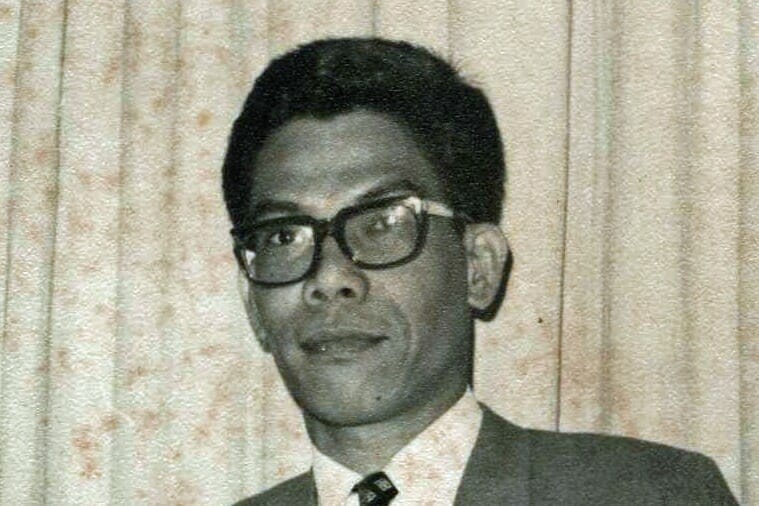

The first writer in question, Guillermo C. De Vega, was born on February 1, 1931 in Rizal Province (Figure 1). He had obtained BA and MA degrees in History from the Manuel L. Quezon University (MLQU) where he was active as a writer in The Quezonian, the official student organ of MLQU. After graduation, his various talents soon attracted the interest of the writer and technocrat Rafael M. Salas (1928-1987), his first patron who also provided the initial tie-up with the young politician Ferdinand E. Marcos. De Vega subsequently took up a scholarship from the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO) at the University of Sindh in Hyderabad, Pakistan, where he obtained a PhD in Political History (ca. 1963). His dissertation was said to be on the socio-cultural history of Pakistan. After his doctoral studies, President Marcos appointed De Vega to the cabinet level post of Presidential Assistant and concurrently as chairman of the Board of Censors for Motion Pictures. Affectionately nicknamed “Gimo,” he was a close confidante and right-hand man of the President. A listing of Filipino writers in English (Tonogbanua, 1984, 62) identifies him as the author of three books: Ferdinand E. Marcos: An Epic (1974), Film and Freedom (1973), and The Lonely Chair (n.d.).

Figure 1: Guillermo “Gimo” De Vega, taken in 1969. Image: Wikipedia Commons

US authorities took a particularly keen interest in De Vega’s dealings with the journalist and former Marcos man, Primitivo “Tibo” Mijares (1931 – c.1978). Some years later, the latter would mysteriously disappear shortly after the publication of his book-length exposé, The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos (1976). De Vega himself was assassinated under questionable if not mysterious circumstances in 1975. According to newspaper reports, he was shot in his office bathroom at the third floor of the executive building in the Malacanang compound. This happened while Marcos himself was in the palace. The suspect, Paulino Arceo, allegedly armed with a snub nosed .38 caliber pistol, shot him several times at close range. The suspect was a former close associate of the above-mentioned Mijares and a producer of a magic show which had been a financial disaster (“High Marcos Aide,” 1975; “Philippine Film Boss,” 1975). According to classified dispatches of the US Embassy in Manila to the US Secretary of State,

We forbear speculation on motivation in devega slaying until more facts available. murder of key presidential aide in malacanang compound, however, will further tarnish new society’s peace-and-order image. devega, through his appointments office, played key role in new society. With president able to appoint all local officials at end 1975, devega’s powers might have increased. It will be most interesting to see whom marcos chooses as devega’s successor. (Embassy Manila, 1975, October 28)

There has been copious outpouring of public grief for slain presidential assistant. President and Mrs. Marcos paid condolence call on devega widow at funeral establishment Oct 29. FYI despite public avowals of grief, devega, a long-time marcos hatchet man with reputation for corruption, appears to have few real mourners, at least among his colleagues. End FYI (Embassy Manila, 1975, October 30)

It is unfortunate that most of De Vega’s remaining archives were destroyed in 2009 during the devastating Tropical Storm Ondoy (intl. name Tropical Storm Ketsana) (R. De Vega. personal communication, June 2018). Today, from a literary point of view, it seems that he will be primarily remembered for his epic on Marcos. However, his poetic feat has almost always subsequently been set in unfavourable contrast with the more seasoned poet Alejandrino Hufana’s tonal epic on Imelda which was published a year after his own (Hufana, 1975). See for example, Franz Arcellana’s comparison of the two epics as the subject of his speech for the Brig. Gen. Hans M. Menzi Professorial Chair for Creative Writing (Arcellana, 1977). Incidentally, Hufana was also the author of a long poetic work entitled, Sieg Heil: An Epic on the Third Reich (1975).

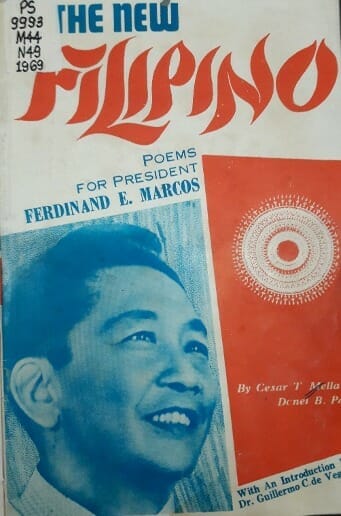

The other court poet to be discussed in this study, Cesar T. Mella, was eleven years younger than De Vega. He was born on April 1, 1942 in Manila but claims to have roots in the town of Magallanes in Sorsogon. Like De Vega, he also graduated from MLQU (AB Journalism) where he served as literary editor of The Quezonian. Beginning in 1964 with his first book of poems entitled Home to my beloved: A volume of enchanting love prose-poems and others, he published in quick succession Fragments of Summer (1965), Love Songs: An Anthology of Love Poems by the Country’s Young Poets (1966), Burst of Love: An Anthology of Love Poems (1966), The Fragrant Sky: Selected New poems (1967). After firing off this volley of collections of enchanting poetry bursting with love, Mella published Mga Petalya kay Imelda (Petals for Imelda), Poems for Imelda and The New Filipino: Poems in Praise of President Ferdinand E. Marcos (with Donel B. Pacis), all in 1969 (Figure 2). (Marcos was president of the Philippines from 1965-1986.) His book of poems on Imelda boasted an introduction by Secretary of Labor Blas F. Ople and a preface by the poet Alfredo O. Cuenca, Jr. By 1969, Mella had already caught the attention of De Vega who wrote an introduction (dated May 28, 1969) for his collection of Marcos poems. De Vega gives somewhat guarded praise for Mella’s literary output but, given the lamentable “background of political calumnies and prejudices” of the time, he wholeheartedly applauds Mella’s “unabashed championship of the toil and success” of Marcos, “the leader.” “For all said,” as De Vega writes, “in the midst of confusion, we always yearn for something of light and grace. It is embodied in this book.”

Figure 2: Cover of Cesar T. Mella’s The new Filipino (poems in praise of President Ferdinand E. Marcos) (1969)

As a sideline, Mella would also write movie scripts under the pseudonym “Cris Magdiwang.” Some known titles under this name are “Maginoong Karatista” (Gentlemanly Karate Fighter; 1972), “Basco Silang” (1973), “Kamay na Ginto” (Hand of Gold; 1973), “Ako Laban sa Daigdig” (Me Against the World; 1973) and the unforgettable “Isprakenhayt” (1973) (“Cris Magdiwang,” 2020) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Film Poster of “Isprakenhayt.” Cesar T. Mella wrote the screenplay under the pen name “Cris Magdiwang”

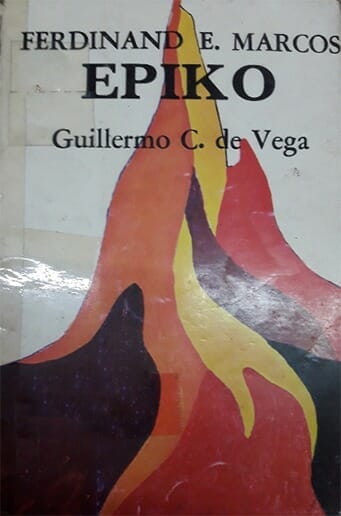

By 1974, De Vega had appointed Mella as president of Konsensus Inc., a “marketing firm” which is recorded as having published De Vega’s, Ferdinand E. Marcos: An Epic (1974) and the poet Alejandrino Hufana’s (1926-2003) Imelda Romualdez Marcos: A Tonal Epic (1975). KONSENSUS also published a Tagalog/Pilipino translation of De Vega’s work entitled Ferdinand E. Marcos: Epiko (1974). (The stated business address of Konsensus was Rm. 207-213 National Press Club, Intramuros, Manila.) Though it is quite obvious that there were translators involved in the latter publication, there is no mention of any of them in the whole volume. (Some of Mella’s associates at the time who were making names for themselves writing in Pilipino were, Virgilio Almario, Lamberto Antonio, and Rogelio Mangahas. Perhaps some of them were involved in this task.) (Figure 4) The blurb on the inside flap of the translation by Ponciano B. Pineda, then director of the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF), simply indicated that, “Naipagtagumpay na lalo ni Dr. de Vega ang kanyang makasining na layon sa pagkakasaling ito ng epiko sa wikang pambansang Pilipino” (Dr. De Vega attained even more success in his artistic objectives through the translation of the epic into the Pilipino national language). The Pilipino edition also included a letter to De Vega from the director of the Bureau of Public Schools, dated November 6, 1974, informing him that the book “has been approved as a library and reference book (social studies) in the secondary schools and college.” Information on the print run of 3,000 copies, prices for the linen, hardcover and softcover editions were likewise indicated.

Figure 4: Cover of the Tagalog Translation of Guillermo de Vega’s Ferdinand E. Marcos: an epic (1974)

The year immediately after the publication of De Vega’s Ferdinand E. Marcos: An Epic (1974), saw the publication of Mella’s poetry book Ricebirds: Selected Poems (1974). (De Vega was 43 and Mella 32 years old when the Marcos epic was published.) According to the blurb on the book-flap of Mella’s collection (probably written by Mella himself),

In fire and spirit, Cesar T. Mella Jr. belongs to the genre of Byron, Tagore and Quasimodo. Although born and bred in Manila over three decades back, his poetry is deeply rooted in the idyllic landscape of ricebirds, cornflowers, sun burnt maidens, thoughtful peasants winnowing rice grains under the fragrant sky.

His book dedication reads, “This book is for Secretary Guillermo C. de Vega, beloved godfather and mentor in life and literature.” For his part, De Vega’s introduction to Mella’s collection in his capacity as literary mentor began with the following sentences,

The poetry of Cesar T. Mella Jr., in this modest volume celebrates a rural world, a primeval landscape of ricebirds, cornflowers, papaya blossoms, green paddies as well as sun burnt maidens winnowing rice grains under “the yellow drops of sun” and peasant men offering rice to the moon, a regional custom inherited from our sturdy forefathers. Browsing over Mella’s work at once brings us to the Philippine countryside made greener and more beautiful by the Green Revolution —- and now the Green Race — envisioned by our First Lady, Mrs. Imelda R. Marcos who is herself a great patroness of arts and their practitioners. (Mella, 1974)

After the assassination of De Vega in 1975, prominent Marcos speechwriter and New Society resident intellectual Adrian E. Cristobal (1932-2007) took Mella under his wing. The post-De Vega period saw him working primarily in public relations and advertising. Further bibliographic information on Mella after this period is hard to come by.

The works of De Vega and Mella can be assumed to be leading representatives of “court poetry” under the Marcos dictatorship. Using contemporary methods in digital humanities, one immediately realizes the potential of using the works of these two individuals in unearthing a possible underlying “poetics” of the Marcos dictatorship. Mella’s poetry collections in English, “Poems for Imelda,” “The New Filipino: Poems in Praise of President Ferdinand E. Marcos” (with Donel B. Pacis) and “Ricebirds: selected poems” (1975) were converted into digital texts and constituted into a single corpus (labeled CTM). For his part, De Vega’s Marcos epic (labeled DVG) was likewise digitized for undertaking comparative analysis. (Software such as Wordsmith tools and Antconc were used to extract the following results.)

One immediately notices that one of the most frequently occurring words in Mella’s stockpile of enchanting lyricisms is “bird.” This occurs in CTM as follows: rice bird (31); black bird(s) (7); corn bird(s) (5); day bird (4); stray bird (3); summer bird (3); heart bird (2); singing bird (2); city bird(s) (1); island bird (1); love bird (1); sad bird (1). DVG has comparatively fewer usages of the same metaphor, but since these are compressed in a narrower span of a single text, they are actually more salient in comparison with CTM: “sunbird” (26); “tiny bird” (1); “tobacco bird” (1). Some related words which occur in CTM with percentages of occurrence much higher than average rates of occurrence in the 100 million word British National Corpus (BNC), and which therefore constitute “keywords” in the text, are as follows: birds (0.26); bird (0.18); sing (0.24); sings (0.08); sings (0.12); ricebirds (0.04); doves; (0.06); blackbirds; (0.05); ricebird (0.03); daybird (0.02). On the other hand, in DVG, some of these salient bird-related words are: sunbirds (0.25); sing (0.11); sings (0.05); phoenix (0.05); wings (0.07); doves (0.03); singing (0.06). (Needless to say, the “sunbird” and the “phoenix” symbolize Ferdinand Marcos himself.)

Taking both corpora together, a test for similarity could be undertaken using n-gram analysis. For the present purposes, an n-gram can be simply defined as a sequence of n contiguous words in a text (a bigram is a sequence of 2 words, a trigram a series of three, a 4-gram a series of four, a 5-gram a series of 5, and so on and so forth). Initial results show that GDV and CTM have a total of 894 shared bigrams (or 2-grams), 161 shared 3-grams, 10 shared 4-grams and 1 shared 5-gram. Despite some of these appearing to be more common than others, all of the n-grams below do not show up in the BNC and some of these are more interesting than others.

The shared 5-gram, “would [1]come [2] again [3] purer [4] than [5],” appears in GDV as, ”triumphs he knew {would [1] come [2] again [3] purer [4] than [5]} tears upon a bloody gravestone”, while it appears in CTM as, “perhaps she whom the heart loves {would [1] come [2] again [3] purer [4] than [5]} rocks grass waves and the falling light”. The 4-gram, “a [1] new [2] filipino [3] has [4],” appears in GDV as, “{a [1] new [2] filipino [3] has [4]} risen from the loamy soil to reach the sun”, while it appears in CTM as, “{a [1] new [2] filipino [3] has [4]} taken over Malacañang.” Such phraseology may simply have been part of New Society verbiage. The shared 4-gram, “a [1] sky [2] of [3] purest [4],” connects with the dominant bird metaphors in GDV and CTM. In GDV it appears as, “gladly will the sunbirds wing to {a [1] sky [2] of [3] purest [4]} blue”, which in turn appears in CTM as, “like a stray bird nests in {a [1] sky [2] of [3] purest [4]} black .” The 4-gram turn of phrase, “for [1] the [2] absent [3] god [4],” turns up in GDV as, “wailing sunbirds waiting {for [1] the [2] absent [3] god [4]}”, and in CTM as “dried loves and human rags looking {for [1] the [2] absent [3] god [4]} in the garbage dung.” Another shared 4-gram poeticism, “forehead [1] brown [2] and [3] smooth [4],” appears in GDV as, “the day the holy water purified the {forehead [1] brown [2] and [3] smooth [4]}”, and in CTM as, “brown fields tilled and plowed on my {forehead [1] brown [2] and [3] smooth [4]}”. The phrase, “the fragrant sky,” which is the title of one of Mella’s poetry collections (1967), turns up in CTM as, “the riceflowers were lonely under the fragrant sky” and in GDV as, “the sterling mark of his leadership inscribed upon the fragrant sky.” Most of the common 2-grams are obviously not unique to the two authors in question. However, some 2-grams of interest include, “affluent [1] breasts [2],” which in GDV occurs in the phrase, “the trembling wetness of dewdrops upon a woman’s {affluent [1] breasts [2]}” and in CTM as, “because she was fragrant and beautiful the landlord plucked her {affluent [1] breasts [2]}” (it is unknown if such a collocation has ever been pronounced in the English language before De Vega and Mella). Also prominent is the 2-gram “april [1] sky [2],” which appears in GDV as, “the clarity of dawn or the transparence of an {april [1] sky [2]}”, and in CTM as, “and they shall live these underprivileged girls under your {april [1] sky [2]}.” Finally, the 2-gram “aureoled [1] in [2]” turns up in GDV as, “the child [Ferdinand Marcos] he came a magnificent atom {aureoled [1] in [2]} a tradition noteworthy for its dogged will of greatness”, and in STM as, “she [Imelda Marcos] must have been Apollinaire’s cornflower {aureoled [1] in [2]} the sunlight of Paris.”

The metaphor of the “lonely chair” occurs in GDV as, “to heart to manhood and to the lonely chair by the Pasig” and in CTM as, “recalls your presence in your absence a lonelier chair waits beside a stone or song sickle ”.

One could hazard that such phrases as, “would come again purer than” or “forehead brown and smooth,” would be almost unique in the English language to the point of being attributable to a single author or inspiration. From the foregoing, it could be that, instead of discovering a common poetics of dictatorship, a probable case of ghost-writing has been unearthed. In what could be a fictionalized confession, Mella wrote the following in one of his better received semi-autobiographical short stories from his collection entitled, “A Priest to the World” (1984),

It was March of 1975, the saddest and leanest year of my life.

My marriage of six years had just failed: my ex boss, a presidential assistant to President Marcos, had just been assassinated and his promise to make me a bureau director – as a reward for ghostwriting a best-selling book for him – died in the wind. Before his death, five months back, he had asked me to resign as public relations officer of a government design office by the sea so that I could work on another book of his, this time on the metaphor of a lonely chair and sadness of a writer in the government bureaucracy. He also requested me to resign, which I did without preamble, from the flourishing marketing firm where I was president due to differences with my so-called colleagues, all his proteges. (Mella 1984, 9)

Looking at some of this admittedly incomplete evidence, one could conclude that De Vega’s poetic tribute to Marcos was actually a piece of ghostwriting by a subordinate. However, it seems unlikely that De Vega had no role at all in the writing of the epic. So it must be stressed that, instead of being a simple case of ghost-writing, some degree of co-authorship, collaboration, revision and editing may well have been involved. Moreover, if De Vega had indeed availed of Mella’s services in producing his panegyric, it could be argued that he was only following in the footsteps of Ferdinand Marcos himself. An excellent study by Miguel Paolo Reyes (2018), tells how the veteran writer Adrian Cristobal Cruz was the real author behind the New Society bibles, Today’s Revolution: Democracy (1971) and Notes on the New Society of the Philippines (1973), which both appeared under Marcos’ name. It is likewise well known that the massive historical tomes of the Tadhana project which appeared with Marcos as the author, were actually written by a team of academics led initially by the one of the most original among Filipino historians, UP professor Zeus A. Salazar (Curaming, 2019). It is an open secret that Marcos’ New Society gave birth to a corrupt culture of intellectual poseurs, speechwriting mercenaries and literary hatchet-men, all paid handsomely for their services the by Filipino taxpayer.

“President Rodrigo Roa Duterte probably cares less for eloquence and literature than for toilet paper.” Image: thongyhod / Shutterstock.com

Conclusion: Dutertian Anti-Poetry

A striking contrast with contemporary Philippine political life can finally be remarked upon.

Marcos wanted to be perceived as a highly-cultured intellectual, historian and author of many books. He wanted his speech and his words to be of the highest eloquence even if these had been crafted by others. He attracted some of the best poets, writers, artists and musicians of the era to serve his regime even as he had some of the best minds of that generation suppressed, tortured, killed and disappeared. He wanted his New Society to appear to be founded on civilized and literate speech and discourse even as the dictatorship he inaugurated trampled upon the most basic of human rights. Ironically, his deeply nouveau riche desire for cultural and social respectability, led to the poisoning and corruption of the literary and cultural life of the nation which has deeply permeated and has arguably continued in the established cultural institutions within and outside the Philippine State.

However, this was not Marcos’ fault alone, this was and is the class pretence of all the established and “respectable” elites in varying degrees from the post-colonial era, leading up to Marcos and the post-Marcos elites of Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino (Kusaka, 2017). It would only be a matter of time before the general populace would grow tired of this fake elite civility and the insistent claims by their “betters” to cultural and intellectual superiority even as their marginalization and exclusion from the social, cultural, political and economic life of the nation continued unabated and intensified.

Today, there are no longer any such pretences. President Rodrigo Roa Duterte probably cares less for eloquence and literature than for toilet paper. No one would dare write an epic for Duterte on the scale which De Vega or Hufana attempted for the Marcos dictatorship at the risk of being laughed out of the room. His brand of authoritarianism has no need for poets and pseudo-philosophers, it only needs court jesters, soldiers and neoliberal technocrats. Who in the contemporary debased political scene gives a damn about epics today? Fancy hifalutin speeches in acrobatic declamatory English à la Marcos (or Senator Miriam Santiago) no longer delight the masses, who probably now suspect that these logorrheic outpourings of ultimately meaningless words are just clever stratagems to distract and hoodwink them. Duterte’s unintelligible outbursts may seem closer to the truth than even any fancy “Habermasian” democratic discoursing with rational trappings in a nation where the languages of the Law and the State is in a foreign language virtually unintelligible to the great majority.

Duterte’s aggressive anti-poetry in broken English, Tagalog and Visayan is the truth of today’s politics. And it is also the unmasked truth of the poetry of all of Marcos’ court poets. In other words, Duterte’s anti-poetry is the truth of the poetry of De Vega, Mella and Hufana. It is also the underlying truth of Philippine elite political discourse. It was only a matter of time before the public discovered that Duterte’s utterances can best be “appreciated” as a form of brutalist anti-poetry, akin to some kinds of “poetry” in its depthless unintelligibility and abysmal incoherence. Since discovering poetry in Duterte’s utterances has become a national pastime of sorts, only two examples will be included here in lieu of a conclusion.

One of the first conversions of Duterte’s “stream of consciousness” speeches into a poetic format was by the writer Mixkaela Villalon who simply cut out a portion of a rambling speech by Duterte dated 9 March 2020 and entitled it “The Kit.” Duterte was talking about the availability of testing kits for the COVID-19 virus. Villalon’s Facebook post, which became viral, is as follows (translations and notes in brackets):

The Kit

By Rodrigo Roa Duterte

To different health center,

But at this time, kung kulang [if these are not enough] They can be brought

To a testing station to RITM [Research Institute for Tropical Medicine].

Kokonti lang kasi, e. [Because these are very few]

The kit

Is the kit.

Meron namang lumalabas pa. [There are still some more coming out]

I think that,

Sabi ko nga – [As I said]

In every epoch

Maybe meron nang una: [Maybe there was a precursor]

Bubonic plague.

Mga gago ang tao no’n [The people at the time were assholes] Tamang tama lang. [Served them right]

Kawawa ‘yung mga tao – [The people were in a pitiful state]

Pero mas kawawa [But the most pitiful were] ‘Yung sa Middle East,[Those in the Middle East] The so-called Roman Empire.

You have read the Inquisition.

Kung may birthmark ka – [If you have a birthmark -]

You are a witch

And you are burned

At stake.

Another frustratingly opaque press conference by Duterte (dated 16 April 2020), still on the COVID-19 virus, also became grist for the poetic mill of the literati. One version, featuring a verbatim rant by Duterte, was posted by Kester Ray Saints with a musical accompaniment on Facebook as follows:

Cobra Kabayo

A spoken word poetry written and performed by Rodrigo Roa Duterte

Sabi ko ‘pag nandiyan na ‘yan bukas

May mga may mga ano na ‘yan na

‘yong iba atat na atat na rin

‘yong gusto nila ilabas ‘yong kanila

‘yong kanila antibodies na

Wala nang proseso antibodies na ‘yong iba

Usually magkuha ka kasi ng uh doon sa patay

Kunan mo ng dugo niya i-inject mo doon sa kabayo

‘yong kabayo kaya niya ng ano ‘yon ang

Inject mo dahan-dahan sa kabayo rin

Huwag naman bigla kasi magka-COVID talaga.

Biktima ‘yan.

Talaga biktima ‘yan

Dahan-dahan lang hanggang ma-immune

Pag marami ng antibodies ‘yong kabayo

Doon na kunin ‘yung maraming…

Dumaan na ‘yan nang kabayo

Kagaya ng kagat ng ahas

Eh sa Mindanao maraming ahas

Pero hindi ko alam na karamihan kobra

Lumipat na dito

Just wait a bit

I said if it is already there tomorrow

It will already have something that the others

Are so impatient

That they want to put out theirs already

What they have are already antibodies

There is no more processing, already antibodies

Usually just get the uh from the dead body

Get his blood and inject it in a horse

The horse can take it

Inject it very, very gently in the horse

Don’t be too sudden because it might really get COVID

It is a victim.

Very gently until it becomes immune

When the horse has many antibodies

Then you can get many …

It has passed through the horse

Like a snakebite

Eh, in Mindanao there are many snakes

But I didn’t know that most of the cobras

Have moved here.)

Ramon Guillermo

FORSEA Board Member

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express thanks to the philosopher and scholar Mario de Vega and Rocio A. de Vega for contributions to the writing of this article.

* Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect FORSEA’s editorial stance.

Sources

Arcellana, Francisco. (1977). Poetry and politics (Part I) : the state of original writing in English in the Philippines today. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Cris Magdiwang, Filmography. (2020, April 22). Retrieved from https://www.imdb.com/name/nm2990606/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1

Curaming, Rommel. (2019). Power and Knowledge in Southeast Asia State and Scholars in Indonesia and the Philippines. New York & London: Routledge.

De Vega, Guillermo. (1974). Ferdinand E. Marcos : an epic. Manila: Konsensus, Inc.

De Vega, Guillermo. (1975). Film and freedom : movie censorship in the Philippines. Manila: s.n.

Embassy Manila (1975, October 28). “Presidential Assistant Murdered.” Wikileaks Cable: 1975MANILA15090_b. https://www.wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/1975MANILA15090_b.html

Embassy Manila. (1975, October 30) “De Vega Murder.” Wikileaks Cable: 1975MANILA15254_b. https://www.wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/1975MANILA15254_b.html

High Marcos Aide is Slain in Manila (1975, Oct. 28), The New York Times.

Hufana, Alejandrino. (1975). Imelda Romualdez Marcos : a tonal epic. Manila: Konsensus.

Hufana, Alejandrino. (1975). Sieg Heil : an epic on the third Reich. Quezon City : Tala Pub. Services, c1975.

Kusaka, Wataru. (2017). Moral Politics in the Philippines: Inequality, Democracy and the Urban Poor. Singapore and Sakyo-ku, Kyoto: National University of Singapore Press and Kyoto University Press.

Mella, Cesar. (1964). Home to my beloved ; a volume of enchanting love prose-poems and others. Manila: Vilfran Press.

Mella, Cesar. (1965). Fragments of summer. Manila : Cesar T. Mella Jr.

Mella, Cesar. (1966). Burst of love : an anthology of love poems. Manila: Association of Young Filipino Poets.

Mella, Cesar. (1966). Love songs : an anthology of love poems by the country’s young poets. Quezon City: Association of Young Filipino Poets.

Mella, Cesar. (1967). The fragrant sky : selected new poems. Manila: s.n.

Mella, Cesar. (1969). Mga petalya kay Imelda. Manila: C.T. Mella & Creative Associates.

Mella, Cesar. (1969). Poems for Imelda. Makati: Buenda Commercial Press.

Mella, Cesar. (1969). The new Filipino (poems in praise of Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos). Manila: C.T. Mella & Creative Associates.

Mella, Cesar. (1974). Directory of Filipino writers : past and present. Manila: CTM Enterprises

Mella, Cesar. (1975). Ricebirds : selected poems. S.l: s.n.

Mella, Cesar. (1984). A priest to the world and other prose works. Quezon City : New Day.

Montañez, Kris. (1988). Myth & Court Poetry. In Kris Montañez, The new mass art and literature and other related essays (1974-1987) (69-81). Quezon City: Kalikasan Press.

Philippine Film Boss Killed in His Office (1975, Oct. 28), The Desert Sun.

Reyes, Miguel Paolo. (2018). Producing Ferdinand E. Marcos, the Scholarly Author. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, 66(2), 173-218.

Tonogbanua, Francisco Ghofulpo. (1984). Philippine literature in English. Manila: Delna Enterprises.

Valeros, Florentino, Estrellita Valeros-Gruenberg. (1987). Filipino writers in English : a biographical and bibliographical directory. Quezon City: New Day.